Campus Life in Three Eras

In 1923, a wealthy industrialist from Lincoln County, North Carolina, made a donation to a nearby college that not only named a building after him as a thank-you but also put his name on the whole institution. That industrialist was Daniel Efird Rhyne, and that’s how Lenoir College became Lenoir-Rhyne College.

Any milestone is a good opportunity to take a look at the past and present as a window to the future we hope to create. The Lenoir-Rhyne of 1923 would have looked only vaguely familiar to students 50 years later and would be difficult to recognize today, 100 years later.

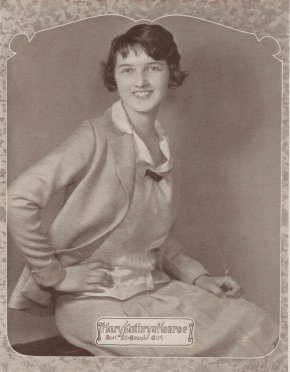

Mary Monroe Gwin ’28 described the 1920s campus to Leslie Keller ’86, an interviewer for “Traces,” an oral history of LR, in 1985. “There was very little paving then on the streets around. There was Old Main and the science building, which was torn down. The old gymnasium, which you know, and Oak View, a frame dormitory for girls, Highland Hall for boys.”

Each building Gwin named is gone now — although students since 1955 are familiar with the auditorium named for Gwyn’s father, P.E. Monroe, president of LR from 1934 to 1949. Between the sites where Highland and Oak View once stood, Fritz-Conrad Hall houses men and women in a single structure. While the landscape and the daily customs change over time, Gwin’s description of the campus atmosphere would be familiar to a Bear of any era.

“Relaxed. Happy, I think,” she said. “There was a good camaraderie among the students.”

MEETING AND GREETING

Countless students have found their lifelong partners at LR, a process made more challenging by the rules of the 1920s, but not impossible.

“You couldn’t have a date unless you had a chaperone. You had to go in a group — ten, fifteen, or twenty — and one faculty member went with you to the movies,” Elizabeth Boliek ’26 explained to “Traces” interviewer Allen Barnhardt ’86. “We weren’t allowed to ride in a car without permission from the dean. You couldn’t even get in a car with a fellow.”

For men, the rules were different. There weren’t any, according to Victor Shuford ’25, who met his wife while out for an off-campus walk. She was sitting in her yard near campus, pretending to read a book. “I gave her a smile and spoke to her, then before I left that afternoon, she drove me in her big, nice car right down to the college,” he told “Traces” interviewer, Lisa Jones Tucker ’86.

Other social activities included attending church services, debates and discussions through the mandatory student literary societies, and after-dinner walks along the Warpath — a driveway that extended from Old Main, where the Rhyne Building stands now, to the corner of Main Avenue and 7th Ave NE.

“We couldn't walk with the boys, but they walked just behind us and we could have many good talks together. Back and forth and back and forth we strolled,” Ethel Yoder, class of 1917, told a “Traces” interviewer in 1977. An attempt to end this custom resulted in a student uproar.

“One evening the girls all gathered in front of Oakview. The boys all came down from Highland Hall and circled around the girls, singing and giving yells,” said Yoder. The walks were allowed to resume.

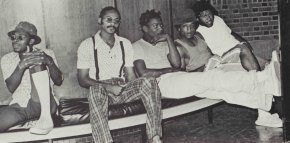

Fifty years later, Mickey Payseur ’73 would take part in a similar scene that became a custom among the fraternities on campus.

“The guys had their fraternity pins, and, if they had a girlfriend they were serious about, they would give their pin to her,” he said. With pinning came a serenade. “The whole fraternity would put on coats and ties. If the girl was in a sorority, her sisters would dress up. Everyone would gather in front of the Lineberger Building at 9 or 10 at night and the sisters and brothers would take turns singing romantic songs to the couple.”

In 2023, social life is much less formal, and dorms are co-ed, with men and women separated by halls instead of buildings. While freshmen follow stricter rules than upperclassmen, those rules are oriented toward safety, security and roommate comfort. However, social life remains focused on larger common spaces.

“Usually, you’ll see people in Joe’s Coffee or Shaw Plaza, and they may have something that catches your interest,” said community health major, Devin Osborne ’24. “Maybe they have a sticker on their computer or a T-shirt that you like, so you start up a conversation.”

CLUBS AND ORGANIZATIONS

Alongside the evolving social scene, many of the organized activities now essential to campus wove themselves into the fabric of LR in the 1920s. For example, Shuford was president of the university’s first marching band, which formed in 1918 but found its footing in the years that followed.

“We played for land sales, political meetings, ball games, parades,” he shared. “When the college got a big grant and changed the name from Lenoir College to Lenoir-Rhyne College, we had a big parade down Main Street, and, of course, it was led by the band, and we had all our pictures on the banners.”

In those years, intercollegiate athletics were limited primarily to baseball and football, but the competition had yet to find the intensity familiar to modern fans. Intramural teams for sports such as basketball and tennis were available to both men and women.

“One summer I was down there, we played a lot of croquet,” Gwin shared. “That was fun. Imagine that now.”

Fifty years later, Title IX was beginning to expand women’s intercollegiate sports options, but intramural offerings were varied and engaging. Reading groups took the place of the literary societies that had been mandatory in the 1920s, and the Playmakers, established in 1926, were going strong.

“The Greek system was very, very popular,” shared Maureen Elliott Teague ’73. Sororities had designated halls in the dorms, and some of the fraternities had houses. “We did community service, formals, and there were some silly things we did during rush. I have wonderful memories of all those events.”

It’s no secret that these days LR offers an expansive and competitive athletics program. Student Life oversees a range of clubs addressing a wide range of interests and offers the option to create new ones. The Campus Activities Board (CAB) offers a full slate of programming each month.

“People are really thankful for the clubs and for CAB because it’s mostly student led,” Osborne explained. “This is a campus where students are coming up with the ideas and making things happen.”

After the Taliban pushed them from their university and homes in August 2021, Afghan refugees have found homes at new institutions all over the world – including LR, where almost a dozen students have found safety and support.

View More

The Visiting Writers Series celebrates 35 years of inspiration, creativity and artistry.

View More